Technical Deep Dive into BitTorrent

In its simplest form, BitTorrent is a very efficient and scalable method of replicating large amounts of data. (Ahm, it’s replication of data, definitely not sharing, you see. xD) . The efficiency and scalability are simply a byproduct of the high percentage utilisation of available network bandwidth, which is made possible through the availability of multiple (100s or even 1000s in some cases) peers from which a file can be downloaded. Without any further pandering, let’s dive straight into the technical nitty-gritty, shall we?

Part 1: Creation of a .torrent file

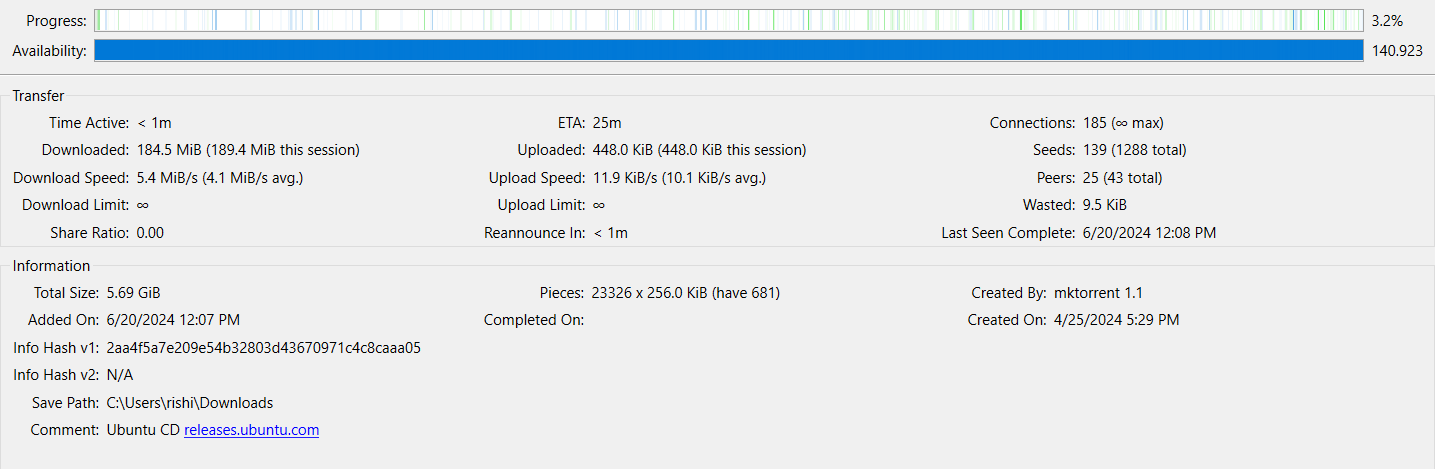

For the file to be distributed via BitTorrent, one needs a .torrent file, which might be apparent to almost all the blog readers (obviously via downloading Linux isos, you see ;p). If one would closely look at a file being downloaded using a BitTorrent client, one would see that the file is never downloaded as a whole, which seems pretty abnormal. Still, for BitTorrent protocol, which is inherently distributed, it would never really make much sense to download a file sequentially. How the distribution works will be explained later, but the first one needs to understand how a client would know how many such distributions are and what their size is. The distributions in this context are known as pieces .

The problem of authenticity of these pieces is now apparent; if a BitTorrent client is receiving data from at times 1000s of different clients, how would it verify the authenticity of the received data? By an SHA-1 hash, where the role of the .torrent file comes into play, not only does it have information about the number of pieces and their size but also the SHA-1 Hash of each of those pieces, which are used to verify file integrity at the time of download.

But when opening the .torrent file, you would also see that if there are multiple folders of educational content (ahm ahm) to be downloaded, the torrent client knows the entire file/folder structure of the data to be downloaded. This is also made possible by the inclusion of file/folder metadata in the .torrent file, whose organisation is in the form of a bencoded dictionary format with keys for fields, as illustrated below.

Bencode is a non-human readable form of encoding that is messy but is essentially a way of encoding dictionaries and keys without using any separators, so quite understandably, it gets messy.

Part 2: Contact a Tracker and begin the file transfer.

Once a .torrent file is made and the person has added it to their client, the process to download the torrent starts with making contact with a Tracker, which can be thought of as a central server keeping a list of all peers participating in a swarm (which is a fancy term to address all the peers involved in distributing the same files). So how would you, a potential peer, join the swarm? This is a question that is answered by the tracker. The tracker provides a list of peers available for file transfer, and your torrent client connects to them.

![]()

A high-level visualisation of the relationship between a peer and a tracker.

2.1 TCP slow start and sub pieces

Wait…why the detour? As I have already described the distribution of a file into pieces, It is also essential to know that BitTorrent uses TCP, and it is thus crucial to always transfer data or else the transfer rate will drop because of the slow start mechanism. What is it?

TCP slow start is simply a network congestion control algorithm that balances the speed of a network connection. Slow start gradually increases the amount of data transmitted until the network’s maximum carrying capacity is found. Hence, when you find your download speeds not straight up jumping to the maximum they could be, it’s simply because of this algorithm.

Hence, to overcome the effects of a slow start, the pieces are further broken into sub-pieces, often about 16 kb in size. This ensures that there are always a number of requests (typically five) for a sub-piece pipeline at any time. When a new sub-piece is downloaded, a new request is sent. Sub-pieces can be downloaded from different peers.

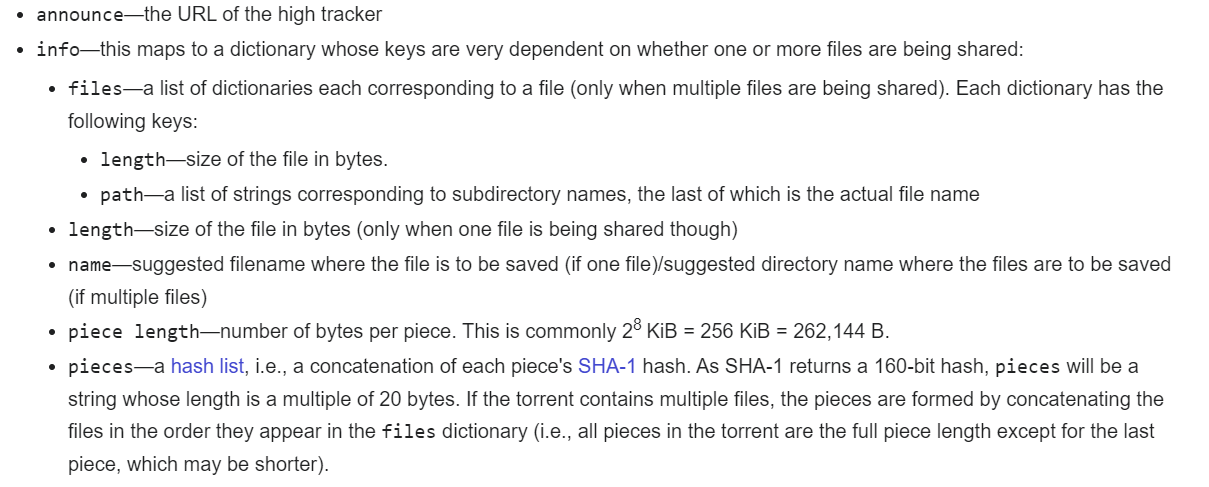

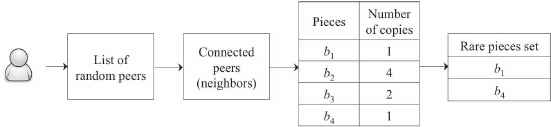

2.2 Piece Selection

However, there are several other problems to be sorted, the primary one being that of minimising piece overlap between peers for efficient utilisation of available bandwidth. As the file that is being transferred is divided into a huge number of pieces at any given time, different peers can have different pieces with them that they are either downloading or sharing. But think if, say, there are four peers, and 2 of those have pieces identical to each other, then they are left out of the file transfer process as they don’t have anything to exchange with each other. Hence, the potential to maximise file transfer rates is missing. This is more apparent from the illustration below :

The peers on the left have a small overlap with each other, as is obvious, while those on the right have a big piece overlap.

Now that we know the piece overlap problem, the obvious way to overcome it is to randomise piece distribution between peers so that a swarm does not become that with big piece overlap bottlenecking download and upload speeds. This is where the BitTorrent piece-picking algorithms come into the picture. The goal of the algorithm is to replicate different pieces on different peers as soon as possible. This will increase the download speed and also make sure that all pieces of a file are somewhere in the network if the seeder leaves. There are multiple policies of the algorithm:

Let’s say you are a new entrant to a BitTorrent swarm looking to download stuff. What do you download? You have multiple options. One is to download any random piece, rare or not; rare doesn’t matter and get going, but you also have the option to download the rarest piece from your peers. What do you do? Downloading the rarest piece can help improve download speeds across the network as the number of peers holding that rare piece increases, and it becomes not so rare, but from the point of view of the new entrant, if it requests only the rare piece initially, it is possible that the download may stretch for longer as it has started the process itself with a piece with the least availability. Hence, a new peer gets a piece randomly, this is the random first piece policy of the algorithm and after the download of the first piece, the rarest first policy of the BitTorrent architecture kicks in. Apart from all these, finally, let’s say most of the pieces have been downloaded, but there are, say, a couple of pieces left that have a slow transfer rate due to some reason; this is where the endgame mode comes into the picture which helps to get the last chunk of the file as quickly as possibly by broadcasting a request to all the peers. Once a sub-piece arrives, we send a cancel message indicating that we have obtained it, and the peers can disregard the request. Some bandwidth is wasted by this broadcasting, but in practice, this is not very much because of the short period of the endgame mode.

Part 3: Why share? Understanding the BitTorrent economics.

All the peer connections are symmetric, i.e. data flow is not one-way, and each peer can download and upload data simultaneously. But why should I contribute to the swarm and increase my data usage? Why shouldn’t I just maintain a faster download speed? Womp, Womp. If you don’t share data chunks, you won’t receive any. BitTorrent uses a tit for tat exchange scheme. Peers choose those peers to share data with who reciprocate the same. As a BitTorrent peer, you will only have a limited number of upload slots to allocate to other peers. So if you are uploading data to a peer who, in return, is not uploading any data to the network, then BitTorrent will choke the connection with this peer and try to allocate this upload slot to a more cooperative peer.

3.1 How can I participate in a swarm when I have no pieces to trade?

When a new peer joins the network, it doesn’t have pieces to participate in trade, and hence, this tic to tac exchange scheme will prevent it from participating. To avoid and counter such effects, a mechanism called “optimistic unchoking” is used. Periodically, the upload slot will be randomly allocated to an uncooperative peer. This gives new peers a chance to join in and a second chance to previously non-cooperating peers.

3.2 But how do I discover and connect to a peer?

Although BitTorrent creates a decentralised file-sharing system, a crucial centralised point(i.e., tracker) is still needed to maintain the list of peers. The tracker acts as an intermediary that helps all the peers discover each other and also maintains the number of seeders and leechers available for a particular torrent. However, the need for a tracker is only limited to the discovery of peers, and once the connection between peers is established, the need for trackers is not significant, and P2P communication can go on without its need.

3.2.1 Problems with trackers :

If the trackers go down for maintenance or due to technical issues, then the updated lists of peers can’t be fetched, making it difficult to share files. Trackers handle a large number of requests from peers, which creates a significant bandwidth demand on the tracker’s server. Hence, if the publishers are seeding some popular content, they need to invest more in the infrastructure, which might be very costly.

Seems like a bit of a problem to me.

So, Any Solution?

YUP . A trackerless torrent solves the problem. A trackerless refers to a BitTorrent download that operates without relying on a central tracker server for peer discovery. One common method for such decentralised peer discovery is the Distributed Hash Table(DHT).

3.3 Distributed Hash Tables

To eliminate the need for a central tracker, each peer must hold a list similar to that of the tracker. However, the list of trackers is too large to be stored individually with each peer. Hence, each peer maintains a partial list of other peers and the pieces of files they possess. The DHT works with info-hash(i.e. hash of metadata) as the key and peer-information(IP addresses and ports) as the value. Hence, the data for the peer swarm is stored in the DHT. The BitTorrent uses Kademlia as it’s DHT.

Now, let’s try to understand what Kademlia is.

I have tried my best to simplify it as much as possible T-T.

Kademlia DHT

A Neighbourhood Analogy

To understand how the Kademlia works, I have a small analogy to present. Imagine there are 128($2^7$) houses in a neighbourhood, not necessarily all occupied. Each house with a family in it is assigned a pencil, eraser and a copy with seven pages (chosen as 128= $2^7$) and space for two entries per page.

These pages are used to write the phone numbers of the houses(occupied) in the neighbourhood, along with some rules. The rules are stated below :

- Each page says page number ` i’ (

i' from0to6`) can only have the phone number of houses at a distance from $2^i$ and $2^{i+1}$ - 1 - Each page can, at most, have two phone numbers, with no minimum limit.

Now, I want to know details about a household that is 78 units away from my house. Hence, I must try to call a house that is as close as possible to the target house. So now I will dial a number from page no.6 as it contains the phone numbers of houses with a distance of 64 to 127. Now, I dial up one of the numbers out of the two written on the list. It appears that the house I called is at a distance of 14 from the target house. So it will, in turn, again follow a similar procedure, turn up to page 3 of its own list (contains the phone numbers of houses with distances between 8 and 15) and call a house. This process continues until I get closest to/reach the target.

But this is just not it yet. There are some more aspects missing in this analogy.

This distance of ours is assumed to be special. Especially in what sense might be the question in your mind. First, The distance between the two houses whose phone numbers are written on page ` i’ is always at a distance less than $2^i$. How this is possible might be a question in your head.

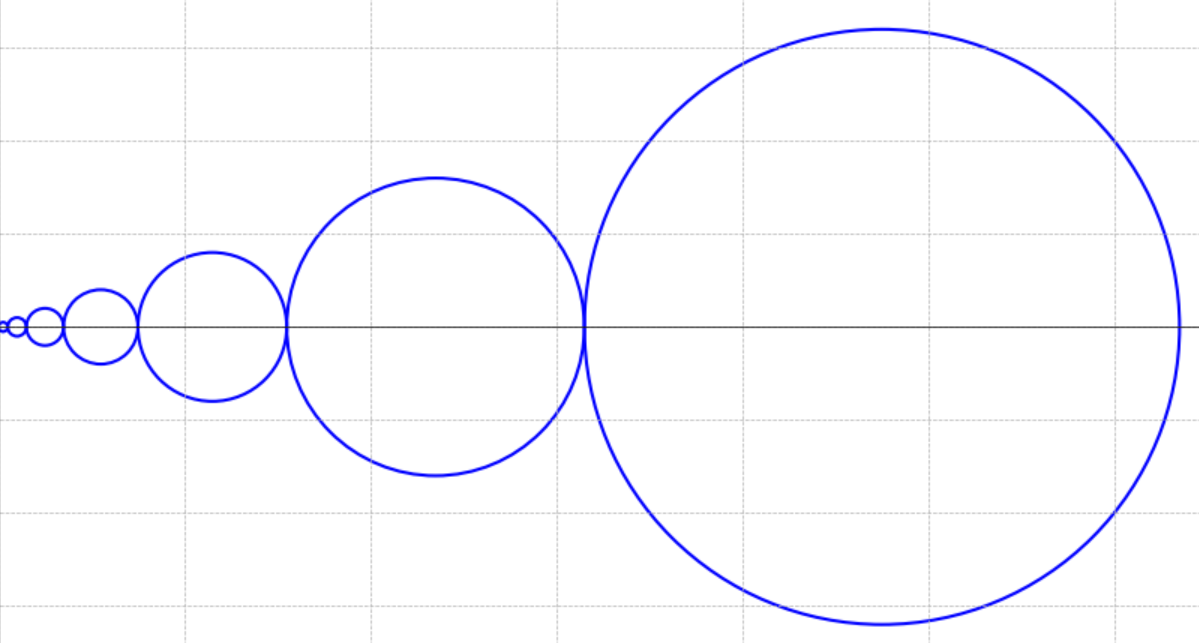

So consider seven circles with diameters of 1,2,4,8,16,32, and 64.

You can see if 2 points lie in a circle, the maximum distance they can be at is the diameter of that circle. Hence, you can imagine the neighbourhood looks like this from each house. Second, no two houses can be equidistant to the same house, i.e. if houses A and B are at a distance of 2 units, then houses A and C or B and C can not be at a distance of 2 units. Don’t worry too much about thinking about implementing this condition geometrically.

You can see if 2 points lie in a circle, the maximum distance they can be at is the diameter of that circle. Hence, you can imagine the neighbourhood looks like this from each house. Second, no two houses can be equidistant to the same house, i.e. if houses A and B are at a distance of 2 units, then houses A and C or B and C can not be at a distance of 2 units. Don’t worry too much about thinking about implementing this condition geometrically.

With these two assumptions in mind, one might think about the purpose of this special distance. It ensures that it takes at max seven calls to reach the desired node (distance reduces geometrically).

Another advantage is that our target can be uniquely identified by distance from the current house, as no other house is at the same distance from the current one.

Now, there is one last aspect of the algorithm analogy to make use of our limited copy space to the full extent.

If initially, when I called the house on page no 6, as this house is at a distance of greater than 64 from my house hence, my house is also at a distance greater than 64 from this house(obvious actually), so if this house were to store my number, it would store it in the page 6 of its notebook. Now, considering you can only store two phone numbers on each page, it is in your best interest to store the phone numbers of houses that are active(actively picking up your call). So now, if this house which I initially called had less than two numbers written on its page 6, it will note my number with the time of contact.

If it already has two contacts, it will now contact the phone that was least recently called. Now, there are two possibilities :

1) This least recently contacted house doesn’t pick up the call, hence proving to have become inactive. In this case, this house will save my number.

2) This least recently contacted house picks up the call, proving that it is still active. In this case, my number will not be saved, and the time of contact of this least recently contacted house will be updated to most recently contacted.

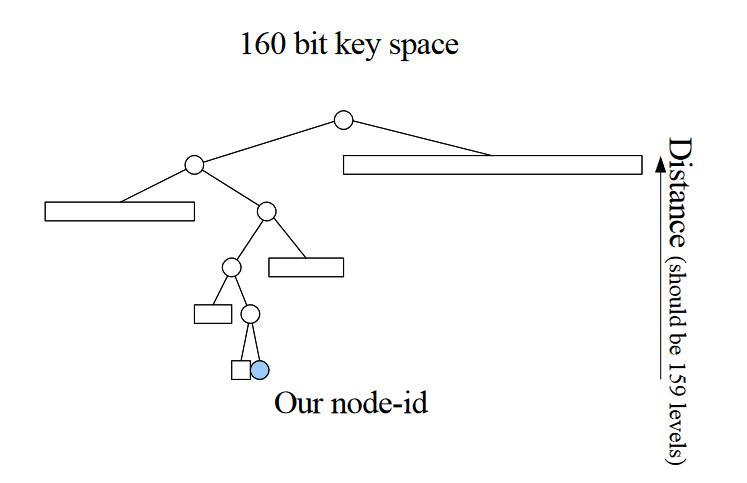

Now in the actual Kademlia DHT, these houses are basically the hash-value, and instead of 128($2^7$) possibilities, we have $2^{160}$ possibilities as we use 160-bit space. The distance between the hashes is calculated by XORing them, and it follows the properties mentioned above. The seven pages of the above notebook, in actuality, are 160 different lists called K-buckets, where K corresponds to the maximum number of entries in each list(in the above analogy, it was 2). Now, let’s formally define the Kademlia DHT.

Kademlia DHT

The Kademlia DHT uses a 160-bit space, i.e. hashes of metadata will have 160-bits in it ( , e.g., SHA-1 ). Let us call this 160-bit space key space. Each participating computer is called a node and is assigned an ID(called node ID) in the key space.

The <key, value> pairs are stored on nodes that are close to the key values. This closeness is defined by the XOR Distance. | Term | Definition | |————–|—————————————————————————-| | Xor Distance | The distance between a node and the key is defined as their bitwise exclusive or (XOR). |

Why XOR distance, though? Well, consider a 4-bit-binary number 1001. If this is the target to be reached, what is the most natural way to select from all 4-bit binary numbers ($2^4$ numbers)? Start from the leftmost bit and drop the numbers from consideration if their bit doesn’t match. So all numbers with 0xxx will be dropped, and 1xxx will only be considered, so in one go, we dropped eight numbers. Now again, we repeat this process for the second leftmost bit and drop the numbers with bits as 01xx, hence again dropping four numbers from consideration. Now, repeating the same process two more times, we will reach the target. So, it can be said that for an n-bit number in n steps, we can reach the target by comparing whether the leftmost bit at each step matches our target or not. Now, how does XOR distance facilitate us in this comparison? Here is the XOR table before I explain further :

| A | B | A ⊕ B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

Now, as we can say, for the same bit in two numbers, A & B, the XOR operator results in 0. So, we can clearly state that the more the bits(from the leftmost end) of the node match with the target, the lesser the value of XOR distance it will assume.

Kademlia stores data about nodes in the lists called $k$-Buckets. Each bucket ,indexed with i : 0 $\leq i <$ 160 , stores triples ==<IP Address , Port Number and Node ID>== for nodes of distance between $2^i$ and $2^{i+1}$ . For closer buckets, i.e. smaller $i$, the bucket can sometimes be empty. For large values of $i$, the bucket might contain up to $k$ in triples.

What $k$ signifies is the maximum number of numbers triples stored in a bucket. The number $k$ is chosen so that any given $k$ nodes are very unlikely to fail (stop replying to requests) within an hour. Generally, the $k$ is taken to be 20.

Now we have information stored on the nodes, let’s understand how the lookup takes place.

The lookup starts from the very first $k$-bucket_ for the node closest to the key(called target.). If the target node is not found in the closest $k$-bucket, the initiating node queries nodes in the next closest $k$-bucket. As the distance used is the ==XOR Distance==, each step increases the common prefix between the node and the key by at least one. Hence, this process continues until the initiating node reaches the closest node to the target.

Each node has a <key, value> pair list for the closest keys, and it is stored in its local storage (different from DHT). Hence, the value for the key from the closest node to the target is fetched from this list.

This is how the trackerless torrent is able to share data chunks without a central system.