Linux Demystified is a blog series by Programming Club IIT Kanpur, covering all the major components of a Linux distribution. This series is not an introduction on how to install/use Linux, nor a comparison between various Linux distributions, rather an explainer on what makes Linux so customizable and powerful. At the end of this series one would be able to customize their own OS, appreciate the differences and pick from the options available at every small level of an Operating System. Although, a complete beginner would easily be able to go through all the blogs in this series, an amateur Linux user may better appreciate and relate to them.

This is the second in the series of blogs, click here to read the first one

Scroll down to the end, if you want to skip the theory, which may feel a bit boring at first.

The Booting process of a computer has seen an evolution of its own. Developers started using the word “Boot” from “Bootstrap” which in turn was a concise way of saying “to pull oneself up by one’s bootstraps”. What does the term mean?

Most softwares are loaded on a computer by other softwares already running on the computer, but where does it all start? Making bits of ordered hardware pieces synchronize together and kickstart a working digital realm, is what Bootstraping is. Let’s start from the same.

Suppose you press the power button, the first component that fires up is the CPU (new to you, right?). Since no task has yet been assigned to it, the CPU runs an instruction in memory that loads the BIOS.

BIOS and UEFI

The key components of a bootloader include the basic input/output system (BIOS), firmware found in the Read-Only Memory (ROM) of a PC. When the PC is turned on, the BIOS runs before any other program runs.

BIOS can boot from drives of less than 2 TB. As 3+ TB drives are now standard, a system with a BIOS can’t boot from them. BIOS runs in 16-bit processor mode and has only 1 MB of space to execute. It can’t initialize multiple hardware devices at once, thus leading to a slow booting process.

…Your system might invoke UEFI instead…

The evolving requirements of computer users have led to the creation of a modern successor to BIOS.

UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) is a mini operating system that loads the bootloader in the memory before it executes additional operational routines.

While it shares some similarities with BIOS, several key differences have led many to consider UEFI as an extension rather than a replacement for traditional BIOS.

UEFI provides the feature of Secure Boot. It allows only authentic drivers and services to load at boot time, to make sure that no malware can be loaded at computer startup. It also requires drivers and the Kernel to have a digital signature, which makes it an effective tool in countering piracy and boot-sector malware. UEFI can run in 32-bit or 64-bit mode and has more addressable address space than BIOS, which means your boot process is faster. Since UEFI can run in 32-bit and 64-bit mode, it provides a better UI configuration that has better graphics and also supports mouse cursor.

UEFI doesn’t require a seperate Boot-Loader, and can also operate alongside BIOS, supporting legacy boot, which in turn, makes it compatible with older operating systems.

…But if it doesn’t, should you consider using UEFI instead of BIOS?

Ignition

When BIOS executes, the first thing that it does is the Power-On Self-Test or POST for short. This goes over all the hardware and associated devices and reports faults if it finds any. Following that, the BIOS checks for the Master Boot Record or the MBR which is located in the first sector of the selected boot device. From the MBR, the location of the Boot-Loader is retrieved, which, after being loaded by BIOS into the computer’s RAM, loads the operating system into the main memory.

Unlike BIOS, UEFI doesn’t look for the MBR at all. Instead, it maintains a list of valid boot volumes called EFI Service Partitions. During the POST procedure, the UEFI firmware scans all of the bootable storage devices that are connected to the system, including external devices which is why you can use a pen drive as bootable.

It looks for a valid GUID Partition Table (GPT), which is an improvement over MBR. Unlike the Master Boot Record, GPT doesn’t contain a Boot-Loader. The firmware itself scans the GPT to find an EFI Service Partition to boot from, and directly loads the OS from the correct partition. If it fails to find one, it goes back to the BIOS-type Booting process called ‘Legacy Boot’. So yes, if your device is supportive, opt for UEFI, which is an extension to BIOS.

This “small” program (talking about BIOS here) runs a power-on self-test (POST) to check that devices the computer will rely on are functioning properly. This includes all the hardware and external devices associated with the computer.

If anything fails, it gives error messages in the form of beeps. If the computer fails the POST, the computer may generate a beep code telling the user the source of the problem else the computer may give a single beep (some computers may beep twice) as it starts,

…with the BIOS/UEFI initiating the bootloader.

Take Off

When turned on, a computer has a clear state. This means that there are no programs in its memory and that its components cannot be accessed. A bootloader helps to load the operating system and the runtime environment to add programs to memory and provide access for components. It also initiates the startup process, and pass control to the kernel, which then initializes the operating system.

Depending upon your system, a bootloader will, well, load up…

There are multiple distributions of bootloaders available, most common ones are GRUB (developed under GNU), GRUB Legacy (older GRUB, not actively developed), LILO (Linux Loader, not actively developed), rEFIt (MacOS Bootloader), and ntldr (Previous Windows Bootloader).

…taking your system from a power-on state to a usable state.

Actually BIOS has already “woken” up the peripherals of the system. The Bootloader steps in to make all components, a system. It now runs “startup code”, whose main duty is to prepare the execution environment for the applications written in higher-level languages. It allocates space for and copies all the global variables in the code into the RAM, initiates stack and stack pointer, heap and calls the main function in the programs to be executed.

At this point, your system is ready to do anything. But continuing on, the Bootloader sets up the OS on your device. It cranks up regular unit tests, and loads device drivers and starts the kernel…

As mentioned in the previous blog Linux is just the Kernel, not the operating system.

But what is a kernel?

A kernel is the core part of any OS that is responsible for managing system resources, such as the CPU, the system memory, storage, and hardware devices. It provides the interfaces that allow user-mode application software, such as word processors, graphics programs, and even games to access system resources in a safe, governed, manner.

The Linux kernel uses a monolithic structure, that is, all operating system services (file system, device drivers, and virtualization) run inside kernel space and all user applications (word processor, spreadsheet, etc.) run in userspace. These userspace applications will communicate with the kernel via a defined interface and use this to access the advanced features of the operating system.

Latest is greatest?

Enough of the abbreviations, what do I do with this?

Well, the above description was independent of the Operating System, except maybe the bootloader. Let’s see this in action —

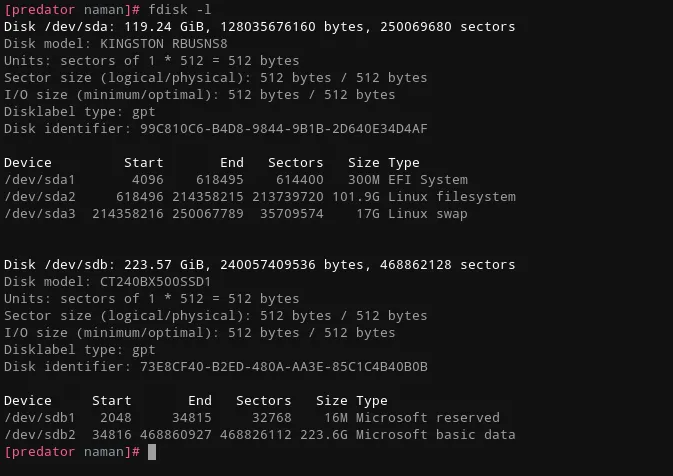

The image above depicts a typical hard disk layout, I have two disks labelled sda and sdb. The partitions in each of the disks are numbered sequentially.

The first thing to notice is the disklabel type — Since my laptop is rather modern (not quite), it supports UEFI. Hence the partition table is GPT.

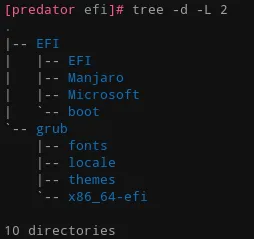

Next, let’s have a look at the partition /dev/sda1. It’s type EFI System hints that it maintains a list of boot volumes. For me it is mounted at /boot/efi, so let’s go there.

It contains grub (which is the bootloader) and the .efi files for the two operating systems installed — Manjaro Linux and Windows.

One more thing to notice are the directories fonts and themes inside grub. Yes, grub the bootloader can be customized! Checkout the file /etc/default/grub (or equivalent for other distributions) which can be modified to customize grub.

This is where the power of Linux can be seen. Although bootloaders are present in all Operating Systems, what if you want your computer to greet you with a message right after pressing the power button?

Note that, a bootloader (like grub) can be used to boot any Operating System if there are multiple installed. This simply does not work with the Windows bootloader, infact, Windows notoriously removes the grub directory from the EFI partition if you install it after installing a Linux Distro.

P.S. Don’t worry about other terms in the above image — filesystem, swap and sectors, we will hopefully cover them in upcoming blogs

Authors: Abhishek Shree, B Anshuman, Pratyush Gupta, Akhil Agrawal, Shivam Mishra, Naman Gupta

Editor: Naman Gupta

Design: Aditya Subramanian