Merkle Trees & its Application in VCS

Introduction: Why Merkle Trees Should Be Your New Obsession

Picture this: You’re at a tech conference afterparty, and someone asks, “So, what’s the most underrated concept in computer science?” While others mumble about machine learning or quantum computing, you confidently declare, “Merkle trees, of course!” Watch as jaws drop and eyebrows raise in admiration (or confusion).

But seriously, folks, Merkle trees are the unsung heroes of our digital world - you don’t see them, but without them, the whole show falls apart. From securing your Bitcoin transactions to ensuring your Git commits are tamper-proof, Merkle trees are the silent guardians of data integrity.

So,let’s dive into the fascinating world of Merkle trees – where every leaf tells a story, and every branch holds a secret!

Chapter 1: Beginnings

1.1 What is a Merkle Tree?

A Merkle tree, also known as a binary hash tree is a fundamental data structure in cryptography and computer science. It’s versatile, reliable, and surprisingly useful in unexpected situations.

Named after Ralph Merkle , this clever construct ensures data integrity and verification. It’s widely used in applications such as blockchain technology, distributed systems, and file verification.

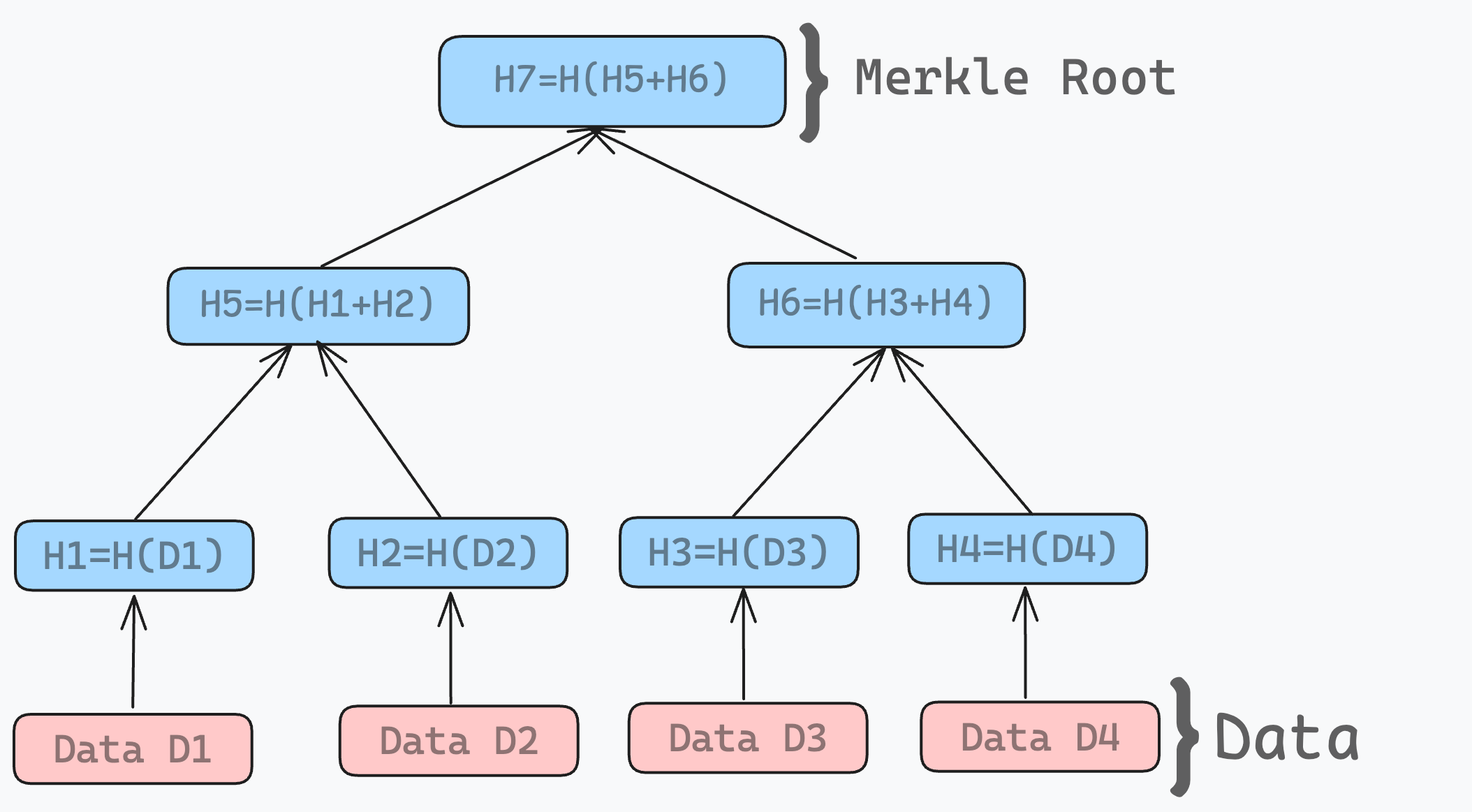

So, what exactly is this magical tree? A Merkle tree is a binary hash tree in which each parent node (non-leaf node) is a cryptographic hash of concatenated values of its child nodes. In simpler words, leaf nodes of a Merkle tree contain the cryptographic hash of the original data, and every subsequent parent node is a hash value of concatenated hashes. Two processes are repeatedly implemented to construct a binary tree, namely: pairing and hashing.

Let’s break down the basic structure, or as I like to call it, “Anatomy of a Crypto-Forest”:

-

Leaves: The bottom layer of the tree. These leaf nodes represent the hash values of the original data nodes. Each leaf contains a cryptographic hash of a data block, ensuring that even a tiny change in the data will result in a wildly different hash value. It’s like nature’s way of saying, “I see what you did there!”

-

Internal Nodes: The middle layers of our tree. Each internal node is a hash value derived from the concatenation of its child nodes’ hashes. Specifically, an internal node is the hash of the left child’s hash concatenated with the right child’s hash.

-

Merkle Root: The top node, the boss of all hashes, the one hash to rule them all. The Merkle root is the topmost node of the tree, representing the cumulative data of all the nodes within the tree. The hash stored in the Merkle root is essentially the fingerprint of the entire dataset.

-

Hash Function: The magic wand that turns data into fixed-size gibberish (in a good way). This essential component in constructing a Merkle tree must have properties such as determinism, pre-image resistance, and collision resistance. It’s so good at its job that even a tiny change in input causes a butterfly effect in the output (hello, avalanche effect!). The hash function ensures the integrity and security of the data represented in the tree.

1.2 Merkle Proof: Verifying Data Integrity with Mathematics

Also known as a Merkle branch or Merkle path, a Merkle proof is a sequence of hashes that can be used to verify the inclusion of a specific leaf (data block) in a Merkle tree.

The key idea is that this sequence of hashes allows anyone to recompute the Merkle root — the unique identifier of the tree. By successfully reconstructing the root using the proof, one can confirm that the leaf is indeed part of the original dataset without needing access to the entire tree.

For example, in the tree given above , the Merkle Proof for H3 is [H4, H5]. We can regenerate the root hash using H3 and its Merkle proof to verify:

H6 = H(H3+H4)

H7 = H(H5+H6)

We can verify whether the generated root hash matches the expected root hash. This process ensures data integrity and confirms that a specific piece of data is part of the original dataset.

This approach also enables efficient operations such as search, insertion, and deletion, all of which can be performed in O(log n) time.

But wait, there’s more! If we dive deeper into the analysis, let’s suppose we have 2n data nodes. To construct a Merkle tree, we need to undergo 2n+1-1 hash operations, which is approximately twice the number if we had to generate hashes for the data nodes only and not construct the tree.

1.3 How Secure is a Merkle Tree? (Spoiler: Very, Though Not Completely Impervious)

Merkle trees are like the Fort Knox of data structures. They’re a secure method for data verification that would make even James Bond jealous.

Here’s how it works: If any data node in the Merkle tree is modified, its corresponding hash will also change. Since each parent node is derived from the hashes of its child nodes, this change propagates upward through the tree, ultimately resulting in a different Merkle root. This ensures that any tampering with the data can be quickly detected by comparing the computed root with the original.

The Merkle root — a single hash at the top of the tree — serves as a compact summary of all the data in the tree. By comparing a newly computed Merkle root to a previously known and trusted one, we can efficiently verify whether any part of the data has been modified.

However, Merkle trees are not completely immune to vulnerabilities. Two known cryptographic threats are the Second Pre-image Attack and the Collision Attack. These attacks target the underlying hash functions and can potentially compromise data integrity if the hash function used is weak or outdated.

To mitigate these risks, Merkle trees rely on strong cryptographic hash functions like SHA-256, which are designed to resist such attacks.

1.3.1 Second Pre-image Attack: Compromising Data Integrity

A second pre-image attack occurs when an attacker is able to find a different input x' that results in the same hash as a known input x, i.e., H(x) = H(x'). This undermines the fundamental assumption of cryptographic hash functions — that it is infeasible to find two distinct inputs that hash to the same output when one of them is known.

Real life example: Consider a blockchain-based voting system where each vote is hashed and included in a Merkle tree. If an attacker can generate a fake vote that results in the same hash as a legitimate one, they could potentially manipulate the system to insert fraudulent data without detection. However, due to the security of the underlying hash function, such an attack is computationally infeasible if a strong hash function (e.g., SHA-256) is used.

Merkle Tree Defense: Merkle trees mitigate this risk by relying on secure hash functions and by making the root hash dependent on all intermediate hashes. Any change in data causes a cascading change in the hash path up to the root. Without knowing the original input, it becomes nearly impossible to construct a different input that results in the same root hash.

1.3.2 Collision Attack: Undermining Hash Uniqueness

A collision attack occurs when an attacker finds two different inputs x and x' such that H(x) = H(x'), without any specific target input in mind. Unlike second pre-image attacks, collisions do not rely on knowledge of a specific input beforehand.

Real life example: Suppose a system uses a Merkle tree to verify document authenticity. An attacker who manages to find two documents that hash to the same value could substitute one for the other, possibly deceiving a digital signature verification process. For instance, this could affect contract integrity or legal documents if a weak hash function is used.

Merkle Tree Defense: Using strong collision-resistant hash functions significantly reduces the feasibility of such attacks. Additionally, in a Merkle tree, each internal node depends on a unique combination of its child hashes, which makes creating a valid collision that results in the same Merkle root extremely difficult.

1.3.3 Strengthening Merkle Trees: Hash Differentiation

To further enhance security, some Merkle tree implementations apply differentiated hashing — using distinct methods for leaf nodes and internal nodes.

How It Works:

- Leaf nodes are hashed using a function like

H'(data)or with a specific prefix (e.g.,H(0x00 || data)). - Internal nodes are hashed as

H(0x01 || left_child_hash || right_child_hash).

This approach ensures that even if an attacker finds a hash collision, they cannot substitute an internal node for a leaf node or vice versa.

Why This Matters: This differentiation prevents structural ambiguities within the Merkle tree and strengthens its resistance against substitution-based attacks. It’s particularly important in systems like blockchains, distributed file storage, and versioned data stores, where the structure and position of data significantly affect integrity and authenticity.

In conclusion, Merkle trees are highly secure structures when built on strong cryptographic hash functions. While theoretical attacks like second pre-image and collision attacks exist, their practical impact is minimal with properly designed systems. Enhancements like hash differentiation further harden the structure, making Merkle trees a reliable tool for ensuring data integrity in modern computing systems.

Chapter 2: Application in Real services

Now, you might be thinking, “This is all well and good, but how does this apply to my life?” Well, dear reader, if you’ve ever used Git (and let’s face it, who hasn’t?), you’ve been unknowingly cuddling up to Merkle trees this whole time!

2.1 Version Control System(VCS):

Surprise! Merkle trees lie at the very heart of the most popular version control system -> git! It’s like finding out your favorite childhood toy was actually a sophisticated robot in disguise. Other services like Mercurial employ a hash-based structure similar to Merkle trees, called a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). It’s like the cool cousin of Merkle trees at the family reunion.

2.1.1 Pieces of the puzzle

But before we dive into the Git pool, let’s look at the terminology in the internal structuring of data in Git. It’s like learning a new language, but instead of ordering coffee, you’re organizing code!

At the base level, all the information needed to represent the history of a project is stored in files referenced by the SHA-1 hash of its content that looks something like this:

6ff87c4664981e4397625791c8ea3bbb5f2279a3

Every object consists of three things - a type, a size, and content. The size is simply the size of the contents, and the contents depend on what type of object it is.

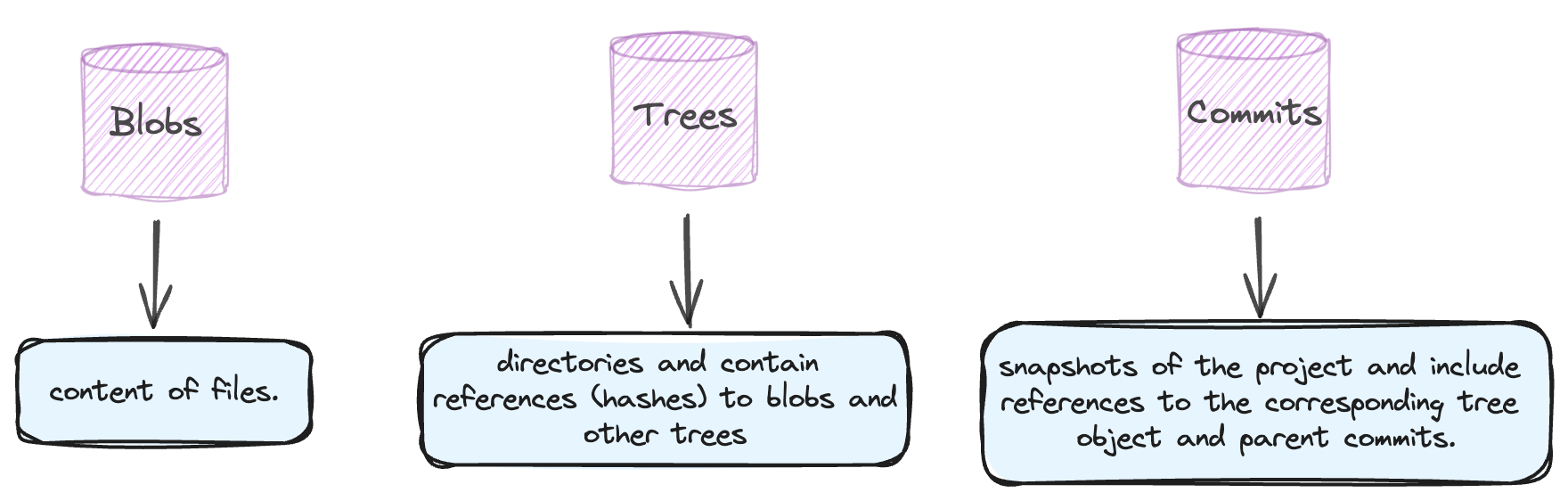

There are four different types of objects in Git’s world:

- Blob

- Tree

- Commit

- Tag

For the purpose of this blog, we’re not going to look at tags, because they’re not essential to understanding the core Merkle tree structure, which is primarily composed of blobs, trees, and commits. However, you can learn about tags here.

Git stores content in a manner similar to a UNIX filesystem, but a bit simplified. All the content in Git is stored as tree and blob objects, with trees corresponding to UNIX directory entries and blobs corresponding more or less to inodes or file contents. A single tree object contains one or more entries, each of which is the SHA-1 hash of a blob or subtree with its associated mode, type, and filename. Confused? Fret not lets break it down one bye one!

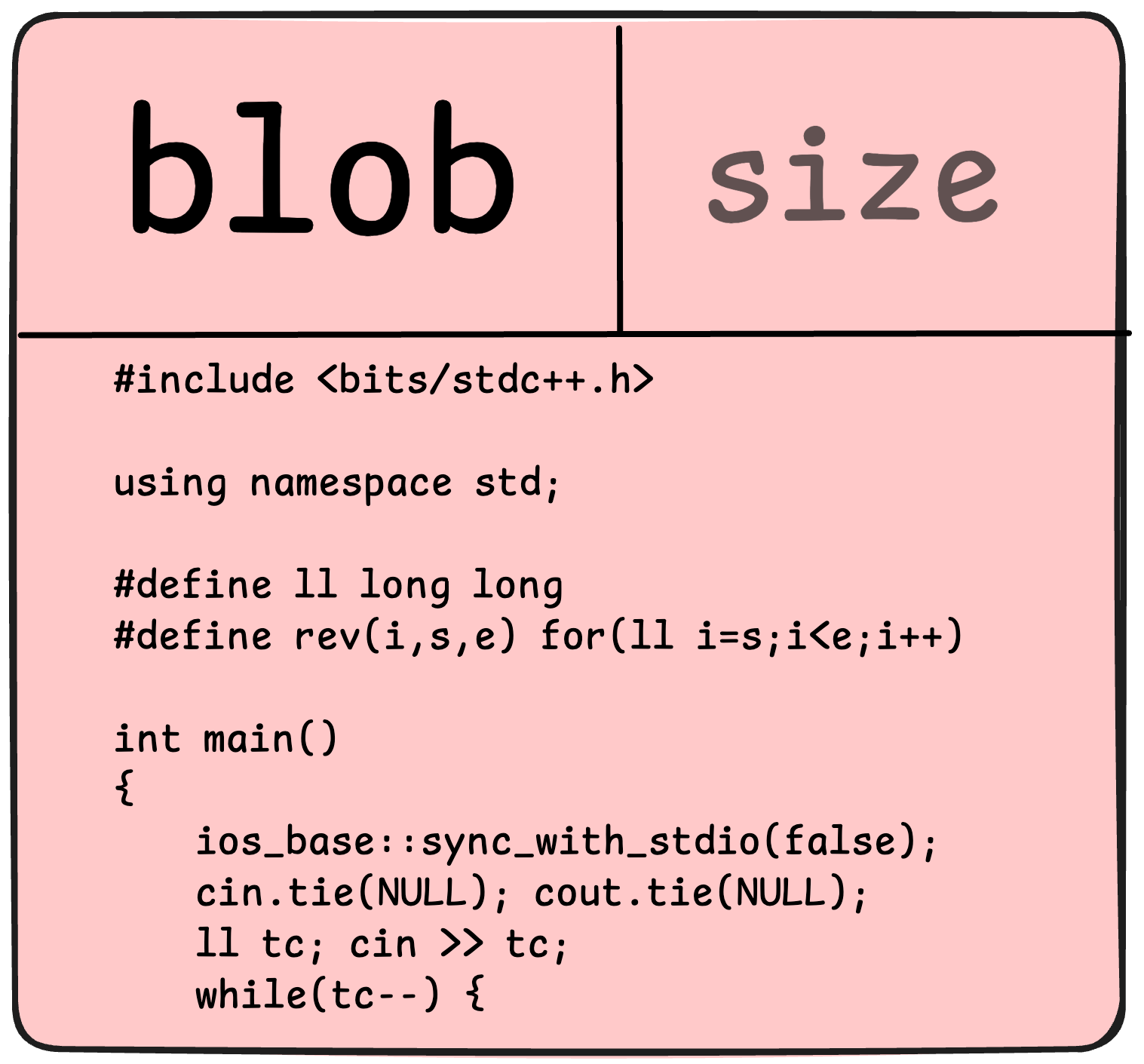

Blob

Binary Large Object or Blob stores the contents of a file

A blob unlike other git objects doesn’t refer to anything else or have attributes of any kind, not even a file name. Yes you read it right, not even file name! This leads to an obvious implication, all files with the same content irrespective of its file-name, version or its location share the same blob. The object is totally independent of its location in the directory tree, and renaming a file does not change the object that file is associated with.

The SHA-1 hash is generated solely based on the file’s content. As a result, if the content is identical, the resulting blob and its hash will be the same, regardless of where the file is located or what it is named.

This feature is part of Git’s efficient data management, allowing it to store content redundantly in terms of physical storage by reusing blobs that represent identical content across different files or versions.

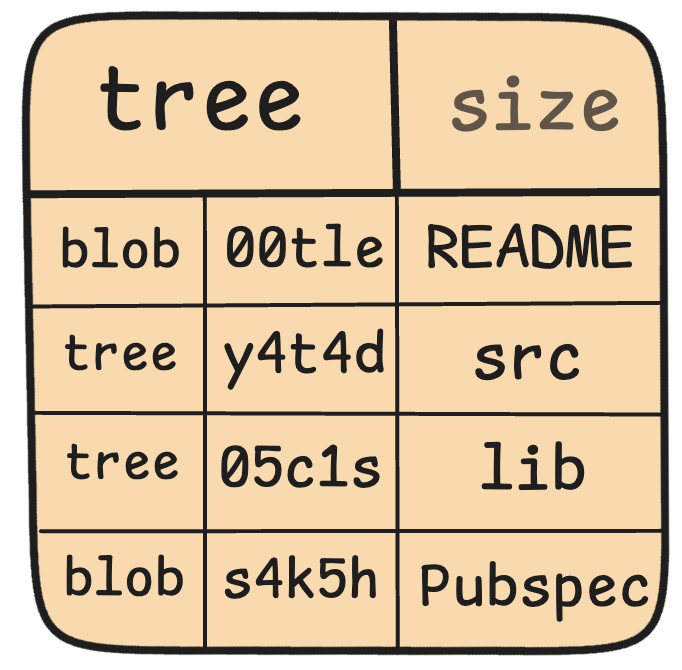

Tree

With Tree, we enter the realm of Merkle Tree. Let’s climb this data structure, shall we?

- A tree object represents a single directory’s contents.

- It’s a list of entries, each with a mode, object type, SHA1 name, and actual name.

- Entries are sorted by name (alphabetical order, not family trees).

An object referenced by a tree may be:

- A blob, representing the contents of a file

- Another tree, representing the contents of a subdirectory

Trees and blobs are named by the SHA1 hash of their contents. This means two trees have the same SHA1 name if and only if their contents (including, recursively, the contents of all subdirectories) are identical. This property allows Git to quickly determine the differences between two related tree objects by ignoring entries with identical object names.

DIY : You can try it yourself using the

git showor thegit ls-treecommand :wink:

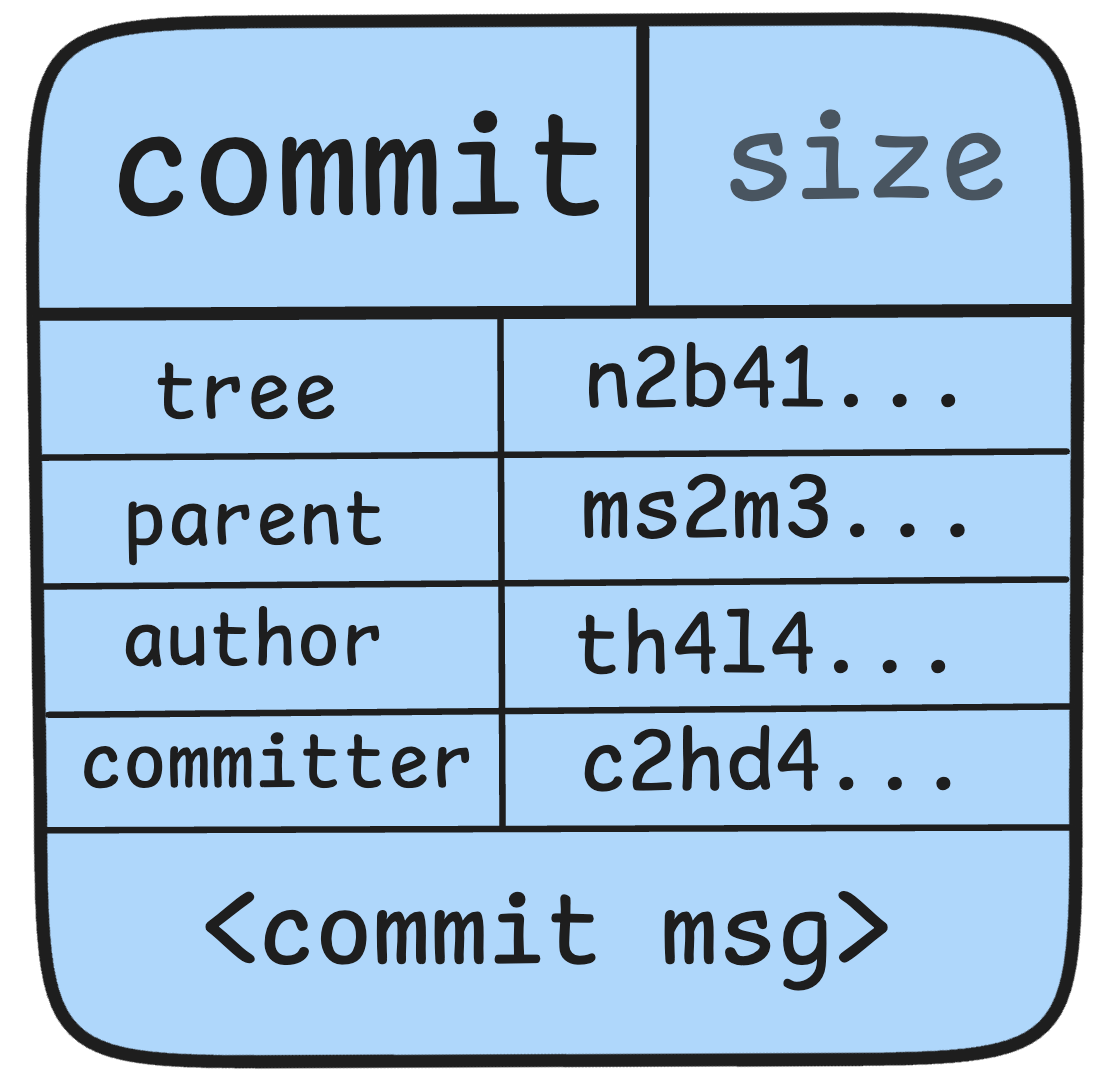

Commit

The commit object is what enables the git to store snapshots of your project at specific points in time.

A commit is defined by:

- A tree: The SHA1 name of a tree object, representing the contents of a directory at a certain point in time.

- Parent(s): The SHA1 name(s) of the immediately previous commit(s) in the project’s history. Most commits have one parent, while merge commits may have multiple. A commit with no parents is called a “root” commit and represents the initial version of a project.

- Author: The name of the person responsible for the change, along with the date.

- Committer: The name of the person who created the commit, with the date. This may differ from the author if someone applied a patch created by another person.

- Commit message: The description attached when the committer created the commit via

git commit -m "<message>"

Importantly, a commit doesn’t contain information about what changed. Changes are calculated by comparing the tree of the current commit with the trees of its parents. Git doesn’t explicitly record file renames, though it can infer them based on file content at different paths.

Commits are typically created using the git commit command, which creates a commit with the current HEAD as its parent and the content in the index as its tree.

In Git, the “mode” of a file specifies its type and permissions. The mode is an essential part of the tree object, indicating how Git should treat the file or directory.The mode is taken from normal UNIX modes but is much less flexible — with only three modes valid for files (blobs), and other modes for directories and submodules:

- Mode: 100644

- This mode indicates a regular file with read/write permissions for the owner, and read-only permissions for the group and others.

- Mode: 100755

- This mode indicates a regular file that is executable. The owner has read/write/execute permissions, and the group and others have read/execute permissions.

- Mode: 120000

- This mode indicates a symbolic link.

- Mode: 040000

- This mode indicates a directory (tree). It’s the bouncer of the Git club, organizing all the other files and directories.

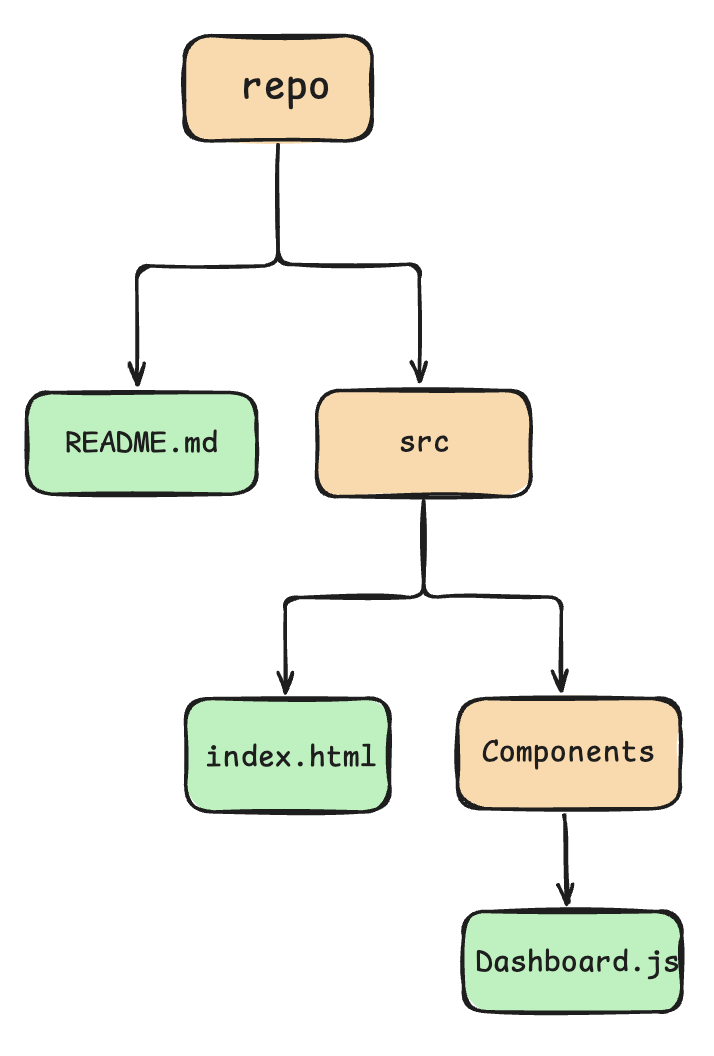

Now that we have all the pieces of the puzzle, lets see how we arrange to form a repo.

Consider a repo which has an initial commit in the following structure:

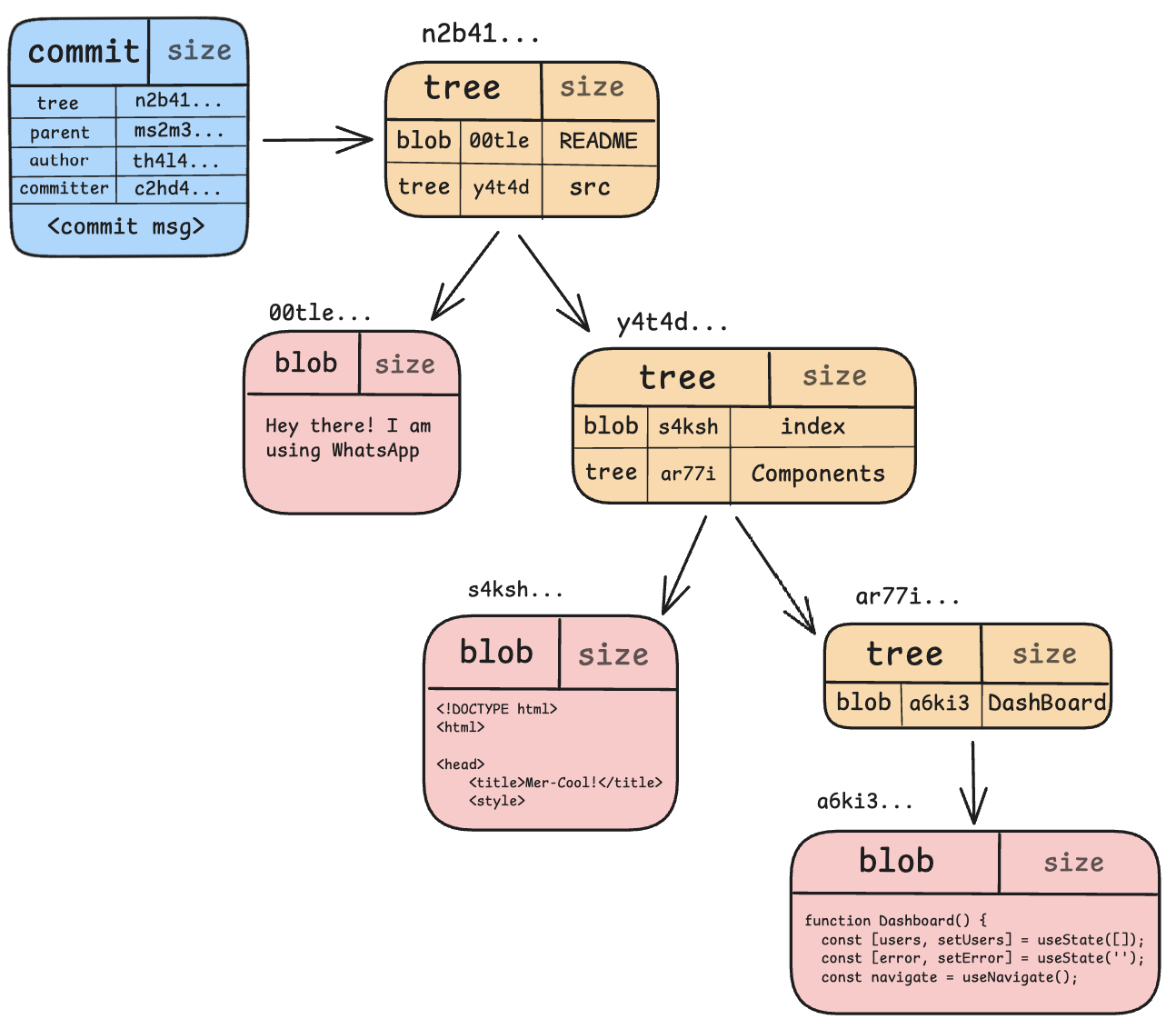

Its corresponding strucutre as stored by git internally:

The above image is a self-explanatory representation of how things are placed under the hood.

Conclusion

Merkle Trees find their way into all corners of modern computing, from Git’s version control to blockchain networks and distributed file systems. Their O(log n) verification complexity makes them practical at scale, whether you’re validating a single file in a repository with millions of commits or proving transaction inclusion in a massive blockchain. Every time you run git commit, you’re participating in a cryptographic protocol that has quietly revolutionized data integrity and collaborative computing.