Throw 2.1 billion transistors in the air, and about 2 years later, 4.2 billion will fall back down, it would take another 2 years to find where they all landed.

This was totally made up, but that rate of doubling has stayed strong for nearly 50 years - Moore’s Law, which says that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles every 2 years. Humanity has made exponential strides in computational power - from the atomic age to the age of information. Only now has the Moore’s Law has hit the tiniest of snags - Quantum Mechanics.

With thinner depletion layers in transistors, electrons will have significant probability to tunnel past potential barriers. This allows leakage current to pass through a transistor, flipping bits in the wrong places. Even a single bit flip by cosmic rays, can cause 737s to crash or voting results to be calculated incorrectly. Determinism, after all, is central to modern computers. So, how do we keep going forward if the roadblock is physics itself? Well, physics might have an answer for it too, a new paradigm called Quantum Computing.

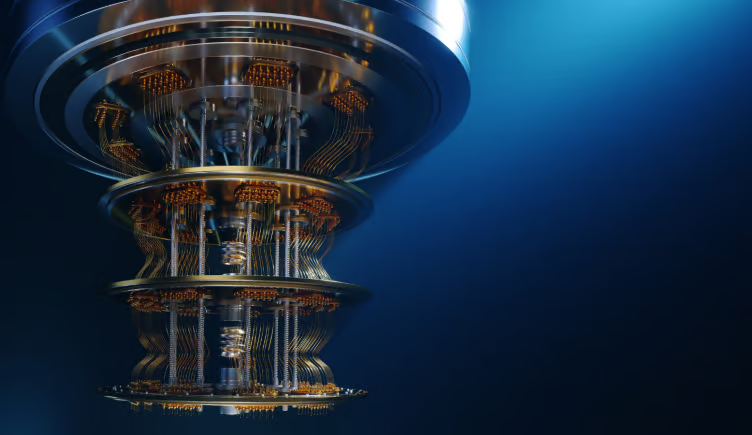

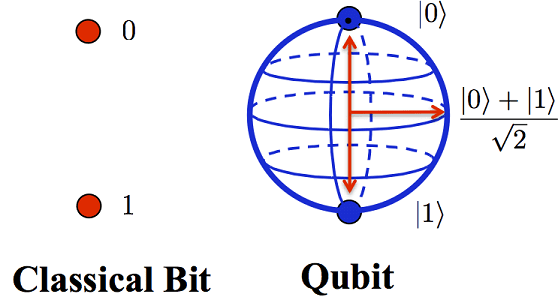

Like classical computing is based on manipulating sequences of 0s and 1s called bits, Quantum Computing is based on manipulating quantum bits, called qubits. A qubit can take values 0, 1 and anything between 0 and 1 (superposition of 0 and 1). Since a single qubit can be a superposition of 0 and 1 at the same time, it can carry exponentially more data as compared to a classical bit. For example, 1 qubit is needed to send as much information as contained by 2 classical bits (made possible by cleverly using entangled qubits and quantum gates, see superdense coding for more details). There is a caveat to this seemingly infinite data storage though. All quantum superpositions collapse to one of the values when someone tries to measure them, with a certain probability associated to what is being measured. Here lies one of the main challenges of quantum computing - to cleverly manipulate qubits to solve computational problems.

In quantum computing notation, 0 is represented as $|0 \rangle$ and 1 as $|{1} \rangle$ (for reasons beyond the scope of this blog). A general qubit can be in superposition of these 2 states and can be represented as $a|{0} \rangle + b|{1} \rangle$, where $a$ and $b$ are complex numbers. The probability of measuring the qubit as $|{0} \rangle$ is $|a|^2$ and $|{1} \rangle$ is $|b|^2$. As sum of probabilities is 1, $|a|^2+|b|^2=1$. In the diagram above, the qubit has equal probability of being measured as $|{0} \rangle$ or $|{1} \rangle$.

Just as classical computers have logic gates like AND OR NOT, there exist quantum gates for manipulation of qubits. Quantum circuits are created using these quantum gates. The details of quantum gates and circuits will be covered in a future post. Here are some of the promises shown by Quantum Computers:

- Grover’s Search Algorithm - this quantum algorithm solves the problem of searching through unstructured data. Consider an unsorted list of $N$ numbers, and we want to find a number $x$ in it which has some unique properties. On a classical computer, you would have to search through the entire list in the worst case scenario, i.e. $O(n)$ time complexity. However, the Grover’s algorithm solves the problem with a time complexity of $O(\sqrt{n})$, a quadratic speed-up from the classical approach. It uses quantum superposition and interference to improve the search time.

-

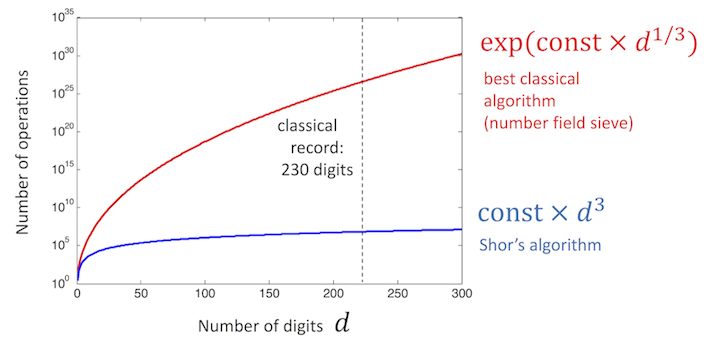

Shor’s Algorithm - a big problem of classical computers is factoring. Currently, we have no better approach to prime factorization of huge numbers other than essentially guessing and checking if a number is a factor. This property is the backbone of modern day encryption - it is extremely difficult to factorize a number which is a product of 2 very huge primes. Enter Shor’s algorithm. Shor’s algorithm runs very efficiently on quantum computers and can easily break all modern day RSA encryptions. But don’t worry just yet - the largest number we have been able to factorize till date on a quantum computer is 21. We still have years to go for the hardware to be mature enough to break the RSA.

![]()

It all just feels like we are back in the 20th century, inventing transistors and computers; networks and communication. Newspapers called the internet a fad back then. And small computers with a percentage of the memory we have today sent man to the moon. As quantum computers go from millikelvins towards absolute zero, that very absolute nature of our information age becomes blurred and fuzzy. What new problems could we solve with a quantum computer? What new Nobel prizes are up for the taking? Could a quantum computer predict the weather? Predict chemical reactions or bridges collapsing? No one can really give a definite answer. All we know is its not all 1s and 0s anymore.